In September I attended one of the largest conferences in archaeology, EAA 2019 in Bern, the 25th meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists. My main reason for attending was that there were an unusual amount of sessions devoted to textile research, which for me as a textile scientist was of course highly relevant and interesting.

There was an entire day on “Ancient Textile Production from an Interdisciplinary Approach: Humanities and Natural Sciences Interwoven for our Understanding of Textiles“ and a half day session on “Household Textiles in and Beyond Viking Age“.

The EAA follows a somewhat unconventional conference format in that there are a dizzying number of simultaneous sessions to choose from, each with at least four or five lectures. Just on the morning of the first day delegates had a choice of 31 separate sessions, some well-attended, others with maybe just a hand-full of delegates in the room.

At the end of each day, most delegates gathered to listen to one of number of keynote lectures. The one I chose was given by Innocent Pikirayi on “Global Change in Africa: What Can Archaeologists Do to Understand the Present Human Condition?“

Other sessions that caught my attention

Apart from the many lectures on textiles, I also attended several sessions on topics that caught my attention: “New Approaches in Bioarchaeology“, “Bending the Arc of History to a Low Carbon Future“, “How Archaeology and Earth Sciences Are Coming Together to Solve Real-world Problems“, “Archaeology, Heritage and Public Value“, “European Origins and Fading Heritage“ and “Challenging Change: Practical Strategies for Horizontal and Vertical Collaboration to Combat Climate Change in the Historic Environment“.

The common denominator, other than textiles, for the sessions I chose was climate change. I found it striking and hopeful just how many researchers addressed climate change and loss of biodiversity. Some centred on adaptation and documentation others grappled with the question of what archaeologists and other heritage professionals can do to make our life sustainable.

Some concrete and common sense suggestions that each and every heritage institution could, and should, implement

- reduction of conference attendances and reviewing necessity of traveling,

- avoiding to fly (joining the movement No Fly Sci),

- enabling video conferencing (some lectures were in fact given via video link),

- promoting slow travel both in conference invitations and institutional policies,

- providing only vegetarian or vegan food at public events,

- reducing waste (the EAA provided a very handy app instead of a printed book of abstracts),

- critically reviewing the ethics of sources of funding, e.g. fossil fuel industry supporting museums and archaeology,

- joining the Climate Heritage Network.

Projects that aim to make heritage management sustainable

There were examples of encouraging projects such as that by Historic Environments Scotland who have a climate change office that has been collecting metrics on the carbon footprint of their historic environments and then taking measures to reduce their energy consumption. Scotland has one of the world’s most ambitious climate targets and Historic Environments Scotland is engaging actively with these targets, changing the way their own operations work and producing a lot of guidance material to help others achieve the same. They also initiated the Climate Heritage Network that will have its launch event on 24th October 2019.

Historical records that exemplify the devastating impact of climate change

There were many calls to use archaeology to highlight the impact of climate change both in the past and today in an effort to draw policy-makers attention to the real emergency of the situation. For example highlighted the session “Fading Heritage“ the plight of archaeological remains in European wetlands that are being drained for agriculture and building projects. The drained wetlands lead to compacted and cracking peat deposits, allowing the influx of oxygen, which in turn enables microbial and fungal growth, and therefore the destruction of archaeological materials. There were shocking examples of the difference in archaeological remains found in wetlands just 100 or even 50 years ago and today. Where in the past decorated bone tools, artefacts and thousands of fish bones were unearthed, the finds that can be made today show that the top surface of any bone tools has vanished beyond recognition and the smaller fish bones are gone. Of course, draining wetlands does not just lead to the destruction of archaeological remains; it has much wider impacts through loss of biodiversity and increased release of greenhouse gases. Nevertheless, shining a light on the loss of archaeological remains can help to mobilise community engagement and maybe change the minds and hearts of one or the other policy-maker or decision-taker to protect vulnerable natural areas.

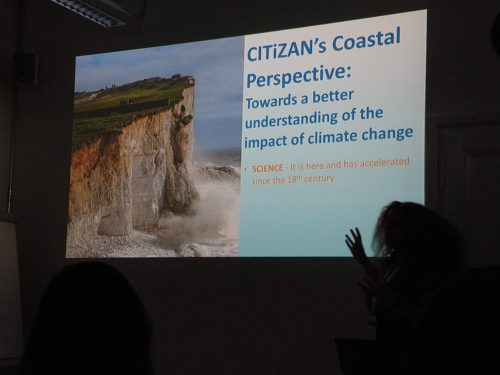

Along those lines were also other lectures that showed the crumbling coastlines of Scotland and England where historic environments are at risk of toppling into the sea, and the Florida coast where the increasing severity of storms and hurricanes is affecting coastal and underwater historic remains. Citizen Science projects are being developed to monitor those rapid changes such as the Heritage Monitor and CHERISH, Climate, Heritage and Environments of Reefs, Islands and Headlands.

Professor Pikirayi’s keynote lecture focussed on his research of the role of water in the development and demise of complex social systems, using three striking case studies: the demise of Lake Chad, the vanishing icecap on Mount Kilimanjaro and the abandoned city Great Zimbabwe.

Heritage professionals as consultants in global development projects

Diane Douglas, Principal Advisor at International Scientific Committee on Risk Preparedness of ICOMOS, gave an insightful talk as she critically reviewed the failings, in terms of social, cultural and environmental issues, of the United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (UN REDD) in Africa.

Vad har våtmarksutdikning med klimatförändringar att göra?

Det finns mycket att läsa om våtmarkens roll i klimatförändring, här är en exempel https://medwet.org/2019/01/med-wetlands-and-climate-change-adaptation/. ”Wetlands sequester some of the largest stores of carbon on the planet, but when disturbed or warmed, they release the three major heat-trapping greenhouse gases carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. Protecting wetlands from human disturbance therefore helps to limit the increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere”